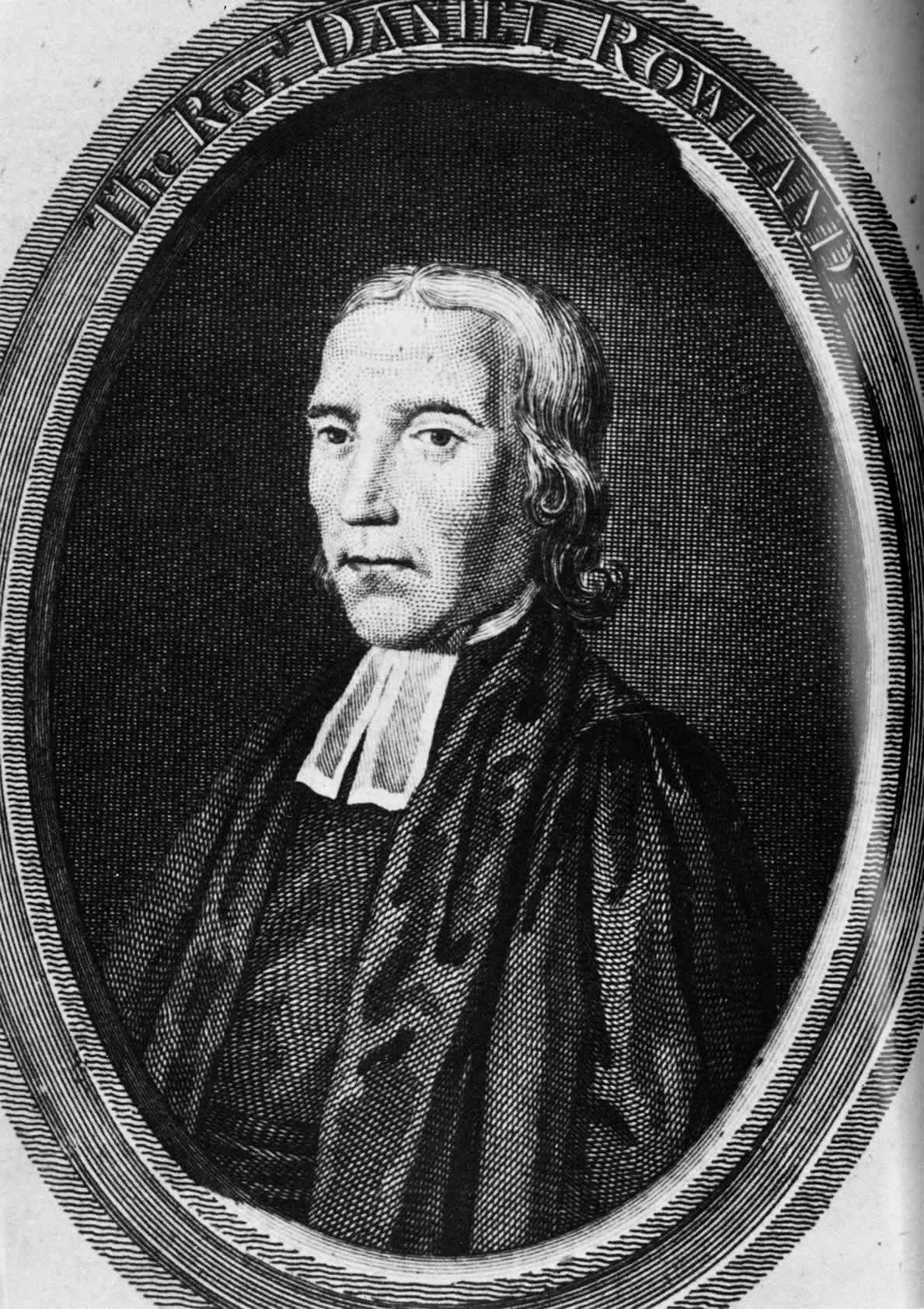

Daniel Rowland

Daniel Rowland (1711-1790) - There is a film on his life under 'films' on this website.

Welsh Anglican Preacher

Wales at the time of Daniel Rowland was still relatively isolated from England. Despite unification under Henry VIII, the Welsh still preserved distinct cultural and historical traditions. Also as Welsh roads were hazardous, people tended to think twice before they visited it. The use of the Welsh language was another isolating factor. Rowland preferred to speak in Welsh and at least early in his ministry, his English was difficult to understand. Griffith Jones, (see this website) who set up his Circulating Schools to teach people to read Welsh, made an interesting point about the language. He said, “There are some advantages peculiar to the Welsh tongue favourable to religion, as being perhaps the chastest in Europe. Its books and writings are free from the infection and deadly venom of Atheism, Deism, Infidelity, Arianism, Popery, lewd plays, immodest romances, and love intrigues; which poison minds, captivate all the senses, and prejudice so many.” This could have been a major reason why the Welsh received Holy Spirit so easily in the coming decades.

The Anglican Church at this time was in bad condition. The clergy were paid so badly that many needed two livings to get by. Bishops appointed the clergy on any basis, rather than on the person being fit for the position. Not only were unfit vicars appointed, but several eminently suitable men were refused ordination. Ignorance and ineptitude were rife in the Church and few taught the Gospel so the people were starved of Truth. Griffith Jones was a shining exception to the rule, but he was had up before the Church authorities for attracting crowds. The situation with the Nonconformists was probably better than with the Anglicans, but there was indolence and ignorance here as well.

One widespread influence at this time was Deism. In his biography on Rowland, Eifion Evans puts it this way. “Human reason was the measure of both truth and reality. Revelation, Scripture, the mysteries of the Christian Faith, miracles, the atonement, and human destiny were all subjected to its evaluation. Whatever was unacceptable or incomprehensible by that standard was deemed to be superstitious or false.” It was going back to the second and third centuries when followers of Plato and Aristotle came into the Church, bringing with them the philosophers’ beliefs that everything had to be explained. The Greek mindset took over from the Hebrew mindset and everything had to be explained. Unfortunately, many religious leaders embraced this ‘new’ teaching and could no longer accept the truth of God's Word without dissecting it and reasoning it; however you cannot reason God or the supernatural. When this teaching came into Wales the Methodists set about to directly oppose it.

Another influence on the Church was formalism. This was an emphasis on ritual rather than emotion; head rather than heart. Formalism pervaded all the churches; except perhaps in Cornwall (see ‘Revivals – Cornwall’ on this website) where the people loved to show emotion. However, in revival Holy Spirit comes and does as He wishes and most of the time He is touching hearts; either making people aware of their sin so that they cry out for mercy or showing them what an amazing sacrifice Jesus performed on the Cross, so they shout out for joy. These shows of emotion are unavoidable when someone’s heart is being touched, but it caused great offence to many clergy during times of revival. (See William Haslam on this website for examples of this.) One of the main avenues of attack against the Methodists was that they were ‘enthusiasts;’ just calling them that was viewed by many to be sufficient criticism. The preachers of the Great Awakening spoke through the mind to the heart of sinners. Nobody can be converted unless their heart is affected; that is one of the main reasons why the Church was in such a dreadful state; because clergy would preach to the mind of the sinner and so no one was converted. Many who were offended by this ‘enthusiasm’ rejected revival because it was not what they were expecting. A Rector’s wife wrote to William Haslam (in the 1860’s) saying that she and her husband had been praying for revival in Norfolk for years, but “if this is a revival, it has come in such a way that I cannot thank God for it.”

Daniel Rowland was probably born in 1711 at a house called Pantybeudy in Nantcwnlle. His father was an Anglican minister although probably not a very useful one. He was rector of Llangeitho and he was also in charge of three other nearby parishes and so was kept busy; he had to walk 18 miles each Sunday to cover his four parishes. As with John Wesley (see this website) Rowland was miraculously saved from death in his childhood. A large stone fell from the top of the chimney onto the spot where he had been sitting only minutes before. He went to school at Pontygido in Cardiganshire where he studied classics and later he went to Hereford Grammar School. As a young man he was good at all sports, active and energetic. Later his daughter described him as being short and having an iron constitution. Also, he never spared himself; he was a fast walker and very passionate.

When Rowland was ordained deacon by the Bishop of St David’s at Duke Street Chapel in London in 1734, he walked all the way there and all the way back! He was appointed curate at Llangeitho and Nantcwnlle. By this time his father had died and his elder brother had taken over these two parishes. The same year he married a local farmer’s daughter and lived on their farm for a year, until his brother married and moved away to Llanddewibrefi when he then moved into the vicarage at Nantcwnlle.

At this time both he and his brother were unsaved. John was notorious for his drinking and Daniel for his levity and worldliness. However, thirty miles to the south was Griffith Jones who was trying to bring to salvation anyone who came within his orbit. His fame had spread and he preached to large congregations. John Owen wrote in 1818 on what happened to Rowland, “One time when he (Jones) was preaching in a churchyard, he saw a young man in the crowd, who appeared restless and rebellious. He observed him for a moment, pointed at him, and with an expression of general compassion, exclaimed, ‘Oh for a word to reach your heart young man!’ Soon it was evident that his restlessness had ceased, and he listened earnestly for the rest of the sermon; and who was this but Daniel Rowland.” It is believed that this happened in Llanddewibrefi.

It is likely that Rowland sat under Jones’ ministry from time to time and he could not have had a better teacher. Rowland was ordained priest soon after this at Abergwili and he was ready for what God had in store for him. The timing all round was perfect as this was just when the Spirit of God began to blow on Wales.

This awakening of Rowland gave him a complete passion for the Word of God and he spent every spare minute in his study. This study was clearly beneficial as his son later commented that he knew most of the Bible by heart. Early in 1738 Howel Harris (see this website) heard that Rowland was studying so hard that ‘he lost his hair and sleep.’ Apart from the mentoring of Jones, Rowland also had the local Nonconformist minister, Philip Pugh as a mentor. Pugh was a fervent Christian, the following quote shows well the type of man he was. “O! may God be pleased to take me in His hand this day, and bring me into His banqueting house, and draw me from every vain thing which saps my faith, cools my love, and makes me unfit for His holy work.”

At this period of his life, Rowland’s preaching brought upon him the nickname of ‘the angry clergyman.’ This was because he was preaching ‘hell and damnation’ and leaving out the compassion and love of God. John Owen writes, “He appeared as if he wished to kindle the fire of hell around the transgressors of God’s law, that he might terrify them. He unfolded the indignation of heaven against sin with amazing clearness, earnestness and vigour.” From the start his preaching had an incredible impact on the hearer and people from all around came to hear him as his fame spread. Clearly, Holy Spirit was anointing his word and opening the hearts of those who came to hear him preach.

At that time people thought that the way to heaven was to attend church and go through the rituals; many believe this even today. However, Rowland was able to make people understand the awfulness of sin and bring them to a place of repentance. He felt such an urgency in his spirit to tell people of the danger he was in; he decided to preach outside his parish; something that was very unpopular in the eighteenth century. It was not until the law was changed around 1870 that a vicar was allowed to preach in another man’s parish without permission. However, Griffith Jones was doing this from time to time and so Rowland thought this precedent enough.

Edward Morgan, one of Rowland’s biographers writes of some advice the wise Phillip Pugh gave to Rowland. “Preach the Gospel to the people, dear Sir, and apply the Balm of Gilead, the blood of Christ, to their spiritual wounds, and show the necessity of faith in the crucified Saviour. ‘I am afraid,’ said Rowland, ‘that I have not the faith myself in its vigour and full exercise.’ ‘Preach on it,’ said Pugh, ‘till you feel it in that way; no doubt it will come. If you go on preaching the law in this manner, you will kill half the people in the country, for you thunder out the curses of the law, and preach in such a terrific manner, that no-one can stand before you.’” Rowland took the advice and from about 1737 he preached God’s saving grace as well, so the people could now go home believing that they were set free through their faith in Christ.

In August 1737 Rowland was invited, probably through Jones, to preach at Defynnog, some 30 miles east of Llangeitho. There he met Howel Harris for the first time; neither knowing about each other’s existence until then. Harris relates “…on hearing the uncommon gifts given him and the amazing power and authority by which he spoke and the effects it had on the people, I was made indeed thankful, and my heart burst with love to God and to him. Here began my acquaintance with him and to all eternity it shall never end.” In October of that year Harris went to visit Rowland and their work together began there.

Despite Harris being a layman (the bishop had refused him ordination,) Rowland allowed him to preach in his church; something that the bishop would not have liked. Rowland was obviously of the same opinion as Richard Baxter, who wrote in the previous century that, “it’s better that men should be disorderly saved, than orderly damned, and that the Church be disorderly preserved than orderly destroyed.”

Crowds were flocking to hear Rowland and Harris; Harris writes that between 400 and 2,000 would hear him speak. Some future leaders were being saved under Harris’ ministry. Howel Davies was converted at one of his meetings in 1737 and he went on to be a curate of Griffith Jones and later the ‘Apostle of Pembrokeshire.’ In 1738 William Williams of Pantycelyn, the hymn writer; accepted Jesus after hearing Harris in Talgarth churchyard. Rowland, Harris, Williams and Davies were the four leaders of the Great Awakening in Wales, working together for many years.

By the end of 1738 Harris comments that the spiritual situation in Wales was similar to the revival in New England that he had read about in an account by Jonathan Edwards. Rowland and Harris were beginning to realise that this was no ordinary work they were doing; the amazing results that they had had from the first days of their ministry could only be through the Hand of God. The huge crowds, the many conversions, the deep awareness of sin and the amazing transformation in people could only be a special work of Holy Spirit. At this time Harris received a letter from George Whitefield (see this website) telling of the revival fires that had started to burn in London.

Harris is always mentioning the power of Rowland’s preaching in his journal. “He had vast power to call all to Christ. Never did I hear such calling, such earnest striving to call all to Christ. Many cried out. Showing that God’s love is eternal and unchangeable. Blessed be God for the amazing gifts and power given to dear brother Rowland. Surely there is no such ministry in Wales. I never heard of like.” He writes of people running to hear the Word at five in the morning and of three sisters who came 40 hard miles to hear Rowland preach.

Both Rowland and Harris had started ‘societies’ as a means of keeping the new converts together in fellowship. This was a subject that was also being considered in England by Wesley and Whitefield. These societies were vital in keeping the fire burning because if the new converts were to go back into their churches then the odds are that with an unsaved vicar at the helm they would soon be called backsliders. John Wesley’s societies eventually became the foundation of the Methodist denomination after his death. For now these societies were used for fellowship and for people to examine one another to ensure that they were leading godly lives and walking on the right path.

Whitefield was becoming quite close to Harris and although he had not yet met Rowland he was in communication with him. Whitefield had an affinity with the Welsh leaders and Wales. Firstly he came from Gloucester that is on the road to Wales from London; secondly, he married a Welsh lady and thirdly they were all very much Calvinistic in their doctrine. The relationship with Whitefield would be beneficial to the Welsh leaders.

John Wesley was to travel to Wales 46 times although some of these were when he was going to and from Ireland; however, he was never to make the same impact that Whitefield did. His first visit was in October 1739 at the request of Harris and he later wrote a letter saying, “I am just come from Wales where there is indeed a great awakening… There is such a simplicity among the Welsh who are waiting for salvation, as I have not found anywhere in England.” Rowland finally met Wesley in Bristol in 1740 and they preached together in Newport in 1741 even though Wesley’s rejection of the doctrine of election meant that there was a doctrinal difference between them. However, Wesley noted, “The spirit of peace and love was in the midst of us.” Both Rowland and Harris were determined that this difference of opinion would not cause a split with Wesley. It was Wesley’s views on free will that prevented him from having a major impact on the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists.

In August 1740 it was agreed between Rowland and Harris that Harris should arrange a meeting of unity between the religious leaders in Wales. In October about eight ministers of different denominations together with eight lay teachers met at Defynnog to explore common ground to work together in the Awakening. They had much in common in that they all were preaching regeneration and justification; they all were concerned for the evangelising of their nation and for the growth and godliness of the new converts. The meeting was not a success. There was divergence on the issue of Church Order and doctrinal differences on ‘assurance’ and ‘opening the heart’ and the Nonconformists were also concerned about the manifestations of Holy Spirit that accompanied the ministry of Rowland, Harris and others; particularly crying out and falling down in the Spirit. God was a God of order! Two spiritual lifestyles, one old and one new, were in tension around the same Gospel message and they went their separate ways.

In February 1741 a new grouping of leaders met to agree a way forward at Llandovery in Carmarthenshire. There were around 30 people including two Anglican ministers and two Nonconformist ministers; the remainder were lay teachers. At this meeting they laid down the basic framework of Welsh Methodism and determined its character, identity and practices for the rest of the century. They agreed on the provision of Welsh Schools and they stood together on the Calvinist side of the great divide with Arminianism. They agreed on doctrine and on the need to continue to attend the parish church (one person dissenting) as the liturgy was pure, whatever the state of the minister. The main achievement was a set of rules for the purpose of managing their affairs and exercising efficient oversight over the Methodist movement in Wales.

All societies were given a copy of the rules. They laid down that they would meet every two months; they were to open their hearts to one another; they should watch over one another’s behaviour and bring issues into the open; they should examine one another; they agreed the doctrines of free grace, weak and strong faith, perseverance in the state of grace, dominion over sin, absolute perfection in Christ, in parts in themselves and allowing of progress by degrees; unity with anyone who is a believer and they were to put aside one day a month for prayer and fasting.

Harris’ undoubted administrative skills were used to organise regular meetings of the societies in the different areas. He emphasised love, simplicity and openness and he appointed leaders over the different areas in South Wales. As in England the Methodists insisted to all that they were part of the Anglican Church. They attended the church for the Sacraments, they subscribed to the Thirty Nine Articles and they used the Anglican Prayer Book.

1741 brought the split in Methodism over the Calvinist – Arminian controversy and over the doctrine of perfectionism. The Wesleys were pro Arminian and pro perfectionism and Whitefield and the leaders in Wales were pro Calvinist and anti-perfectionism. This produced a break between John Wesley and Whitefield, but Rowland always considered that he and Wesley had more in common than what divided them and he and Harris continued to work with him. This same year brought a split between Griffith Jones and the Methodists. He wrote, “Our new itinerant preachers are exceedingly erroneous, harsh, conceited and disorderly” and “very defective in common sense, common manners, and veracity or common honesty.” It seems that much of his opinion comes from hearsay and although some of what he said might have been true, some of it must have been problems with the old accepting the new. Jones also believed his Schools were more important and as he was closely associated with the Methodists he undoubtedly felt that the schools might suffer and so he disowned them. As a result Welsh Methodism lost its respected figurehead and senior statesman. Harris tried to bring reconciliation, but sadly he did not succeed. From this point Jones’ influence on Methodism was a corrective one from without rather than a determinative one within. He was still very much respected by Rowland and Harris and they took note of certain things he said in later sermons.

Rowland had experienced some persecution up until now and Harris had experienced persecution in 1739 and 1740. He had been silenced by constables in Brecon; been arrested and then acquitted at trial in Monmouth; narrowly escaped serious injury from a mob in Montgomeryshire and one of Whitefield’s companions died from mob violence when Harris was speaking at Hay. However, more concerted persecution began in 1741. In August a new vicar was appointed at Ystrad-ffin, specifically to stop Rowland from using it. Up until then it had been neglected as a parish and Rowland had used it as a base for the area, with the permission of the patron of the chapel; but now the doors were closed. A month later Harris was in London and read a periodical called, ‘The New Weekly Miscellany’ that took delight in attacking Methodists. Whitefield and the Wesleys were attacked in turn, but for now it was the turn of Rowland and Harris. They were accused of all sorts of things including making money out of the revival, wanting public applause, holding unlawful meetings and encouraging ‘enthusiasm.’ Rowland and Harris were forced to reply because the bishop sent the periodical to Rowland.

The doors of the churches were often closed to Rowland and the others. Someone who invited Rowland to speak on his area had two vicars refusing to open their churches, with one saying that he had been credibly informed that Rowland was a downright madman. The Methodists were often in personal danger. Harris at Bala was hit with stones and dirt by a furious mob that had surrounded the house where he was preaching. At LLanilar Rowland had stones and other missiles thrown at him so that he had to run for his life. At Aberystwyth a man aimed a gun at Rowland and pulled the trigger, but it did not fire and on another occasion people laid a good plan to blow up Rowland while speaking, but by accident the plan was discovered.

All through this time Rowland was preaching with enormous power and anointing. An Englishman heard him speak, not understanding a word of Welsh, he writes, “I heard much of him, but it could never have entered into my heart to conceive of the mighty energy and power that accompanied his preaching. His words did fly like darts.” Everywhere there were reports of the power and effectiveness of his preaching.

In January 1742, at Dugoedydd, there was a meeting of Methodist leaders, led by Rowland who was now the recognised leader of the Welsh Methodists; to try to sort out some of the perceived problems about Methodism. This gathering of leaders later came to be known as an Association. They wanted Whitefield to attend the meeting, but he couldn’t so he sent a letter instead laying out his ideas. It was agreed to accept Whitefield’s organisational suggestions and to have closer links with England. At the next meeting itinerant preachers (exhorters) were examined and approved, except one. This was done to try to deflect the criticisms that abounded about laymen preaching. In those days the clergy had a very high opinion of themselves and many believed that only they were qualified to preach; there was little understanding of the ‘priesthood of all believers.’ More detailed rules were decided on and were printed, so that the world could see the scriptural validity of the private societies, the irreproachable nature of their activities, and the nature of their discipline. Hopefully, this would stop some of the criticisms about the societies. The rules of these societies were quite strict and much was expected of someone who joined; the aim was to help each person grow in maturity and part of this was a vigorous pursuit of personal holiness. The Methodists were aiming at lively spirituality, as well as strict orthodoxy and morality.

Most of 1742 was a time of difficulty for the leadership as Harris and Rowland fell out. Harris felt that Rowland had his theology wrong on assurance. People were concerned at this breakdown in relationship, but by August it was resolved.

Rowland is still preaching powerfully, he writes in September, “You would all wonder at what we daily see and hear. As for my part I can say I never had such power as I have now every day, mostly to preach. Whole multitudes are under concern. Many of them that were enemies of my doctrine, and way of preaching, do now experimentally understand what He enables me to deliver them from the pulpit. Some confess that they went from home on Sundays with an intent to go to another place of worship, but were, they know not how, carried to Llangeitho.”

He consistently and passionately believed in the sufficiency of Scripture for salvation; Church Councils and prophecy were both dangerous and superfluous. He also thought it advisable for all believers to hold ‘the things of eternity’ constantly in focus. This was also what the Reformers and Puritans of past centuries advocated.

The revival fires became even stronger at the end of 1742 and the start of 1743. Whitefield wrote on hearing Rowland, “The power of God at the Sacrament, under the ministry of Mr Rowland, was enough to make a person’s heart burn within him. At seven in the morning I have seen, perhaps, 10,000 from different parts, in the midst of the sermon, crying ‘glory,’ ‘praise,’ ready to leap for joy.” Through these good times persecution continued. One of the preachers was jailed for being a Methodist but freed at his trial.

Howel Davies was set before the Bishop’s Court for giving communion to people from outside the parish and William Williams was refused to receive full ordination despite having the correct papers etc. The reason given for the refusal was that he was a Methodist and preached outside his parish.

At the end of 1743 everything was good. The revival was continuing and the Methodists in Wales had developed as set of rules and an organisational structure that gave it more respectability. Through doing this they had taken away the cause of one of the main criticisms against them; that they were scripturally in error and disorderly. They were in complete unity over their doctrine; something that the English Methodists weren’t and they were also in unity with Whitefield’s English Methodists. They saw themselves as being exactly like the Reformers of the sixteenth century and the Puritans of the seventeenth. Rowland was the acknowledged head of the group, with Harris as Superintendent in Wales, the chief organiser. Whitefield was there instead of Jones to give advice. To get over another legal minefield; ‘society houses’ were being built, as under the law they needed to have registered buildings so that they could meet without being harassed by their enemies.

The Methodists wanted to show everyone that the societies were not churches, that their itinerant and society preachers, or as they called them, exhorters, were not ministers. They were not a sect, but a people inside the Established Church who were called to reform until either they were heard or turned out.

The societies were handling people at different levels; some could see the dreadfulness of their sin, although they had not yet found Christ through justification by faith; some had found justification but not sanctification, and others had found both. The old law was dead to the Christian, but it was to be used as a ‘rule of life’ for his walk. Through this ‘rule of life’ he comes to rate Christ’s righteousness highly and it drives him to seek more sanctifying grace from God. The people were encouraged to read the Scriptures and leaders were instructed to test them. The success of this depended on the literacy of the people and this is where Griffith Jones’ Circulating Schools were crucial because they taught the people to read. Jones’ Church Catechism was used in the societies as well.

1744 was also a time when the Welsh Methodists began to publish some of their own literature in Welsh, particularly hymns. Rowland published a book of Hymns and William Williams issued his first collection.

Late in this same year a fear went through England over the invasion plans of the Stuart Pretender to the throne. The Welsh Methodists went into prayer and they drew up lists of men who were prepared to defend their country; Howel Davies had a list of 1,500 and Rowland 500. The leaders spoke about the problems of this Catholic threat (which ended in defeat in 1745) and called their people to pray. Prayer was always one of their central themes; Rowland always made time for prayer before he was to speak. A joint prayer initiative came from Scotland to keep one day every three months for two years, set aside for prayer and that there should be thanksgiving each Sunday for the revival and prayers to ask God for it to continue.

Rowland continued his busy schedule in 1745. He was still preaching in power although the powerful manifestations of Holy Spirit that accompanied Rowland’s ministry (and others’) were often misunderstood by the critics. They just could not understand, or would not try to understand that people were crying out in agony because they recognised the full horror of their sinful state, or that they were crying out for joy at the incredible realisation of what Jesus had done for them on the Cross, or that people were laid out on the floor because the power of God had knocked them over. There is no doubt that amongst all this there were people who were acting in the flesh rather than under the power of Holy Spirit. It happened then and it happens today that people mimic what is happening around them, either because they think it is expected or because they want attention. Amongst all the manifestations it was the sermon that took central stage and it was the Word of God that brought home the messages that the people needed to hear. Rowland’s importance though was not just his preaching. At the end of the year William Williams wrote that he was, “a strong pillar in the Church of God, a means to keep the Welsh Methodists from many errors.”

In the midst of all the success a problem was brewing. Harris was becoming more difficult and more critical of Rowland, year by year. There was a dogmatism about him that was unbending. He often reproved Rowland and Whitefield for their ‘levity,’ became critical of their doctrines as ‘legal in some expressions,’ and for being ‘contemptible of the blood.’ He did not keep these disagreements private, but aired them at the Association meetings, with one in October 1746 being particularly stormy. Harris notes that the Association voted for Rowland to take over some of his duties and that they called him an Antinomian and Moravian again. He also wrote that usually when there were disagreements with Rowland he would cry and hug him and all would be well, but this time he was ‘more stiff;’ and things were not resolved. Harris was straying from orthodoxy. Richard Tibbott considered both parties to be at fault; agreeing that Harris’ reproof was timely, but he told Harris that he was sometimes too dogmatic and his subjective judgement resulted in his being unable, “to distinguish between people and their opinions. There is some bad in good men, but it is wrong to regard good men as bad on account of their faults. You failed to distinguish between some and others of those you opposed, and accused all indiscriminately…You were too hasty in taking suspicion for fact.

This situation continued for several years. Rowland and Harris came into direct confrontation with Harris expelling some people from the societies and then Rowland allowing them back in. Another error of Harris’ was that in 1749 he began to travel with a married woman whose prophetic gift blessed Harris. She became his counsellor; replacing his wife in that position. Many tried to reprove him for his folly; including Rowland and Whitefield. In trying to apportion blame in all this it has to be significant that Whitefield, who knew them both well, supported Rowland throughout this time and so we may assume that Harris should take a large portion of the blame for the split that was to soon occur. Harris claimed that his relationship with the prophetess was purely spiritual and he believed it was of God. He ignored the Word of God on the matter, he ignored wise counsel from leaders; he ignored the sensibilities of his wife and the offence he caused to many. Harris was endangering the future of the movement due to a belief that he had a superior relationship with God which meant that he did not need to submit to anyone. Self-righteousness is a common strategy of the enemy to take out leaders; something we need to watch out for.

Following the Association meeting of May 1750 Rowland and Harris, together with their supporters; went their separate ways. Harris’ dictatorial attitude however, soon lost him considerable support, and gradually Welsh Methodism rallied behind Rowland. In one way the split helped the movement as the world was shown that anyone, even a senior leader, who strayed from the stated doctrine, would be disciplined and mutual submission was obligatory amongst them.

The work continued and still, on occasions, extraordinarily powerfully. Rowland visited Bristol in 1751 and he preached with Whitefield to vast crowds. Whitefield visited Wales often and Welsh and English Calvinistic Methodism were seen as one movement. In 1753 the Moravian, John Cennick, wrote his observations on the work in Wales. “I have now been in every county in Wales; and observed everywhere the fruits of the indefatigable labours of Howel Harris, which have been wonderful, though now he has but few with him, and those chiefly about North Wales. I also witnessed a great spirit of devotion through all the Welsh people, and almost an universal respect for the ministers, whether laymen or clergy.”

Harris’ withdrawal had been damaging to the revival as his preaching skills and organisational abilities were much needed. Wales had a shortage of Welsh speaking preachers as it was. However, the work went on as was shown in Whitefield’s comments on his annual circuits of Wales. His 1758 tour was, “one of the most prosperous” that he could remember. “Twice every day, thousands and thousands attended in various towns in South Wales, and on the Sundays the numbers were incredible.”

Rowland preached on! In November 1756 a preacher from North Wales heard him, “He dwelt with such overwhelming, extraordinary thoughts on the greatness and love of God, and the vastness of the Gift, that I was swallowed up in amazement. I did not know if my feet were on the ground. I had no idea where I was, whether it was on earth or in heaven!” During the years to 1762 Rowland’s preaching did not diminish and he also spent time translating some works into Welsh. Over Wales, sometimes Holy Spirit poured out in power and sometimes there were periods when things appeared quieter, but still Holy Spirit was doing an amazing work.

There is little known about Rowland’s home life. He had two sons and four daughters and the oldest son was by this time a priest. He supplemented his income by raising sheep, but with all his ministry work, the burden of the farm, the home and the family must have rested on his wife. For 25 years Daniel had run the parishes with his brother John; John had been vicar and Daniel, curate. In 1760 John drowned and as a snub the bishop appointed Daniel’s own son to be vicar over his father. Daniel’s son John disapproved of his father’s evangelicalism and he made a point of keeping away from Llangeitho; spending his life in Hereford and Shropshire. Shortly afterwards the bishop appointed Isaac Williams to another of Daniel’s parishes and David Davies to the other two.

1762 once again brought full blown revival. A different aspect of this revival was the singing. William Williams had brought out another collection of hymns, largely about longing for God’s presence, which proved very popular. In retrospect, people spoke of the time preceding the 1762 revival as ‘the long winter.’ This is difficult to understand in view of the amazing things that went on before; perhaps the people who thought this were not around in the 1730’s and so could not compare. Even the 1740’s and 1750’s seemed to be full of what we would be thrilled to see in our time, so what must it have been like in 1762?

William Williams wrote about a prayer meeting he was at where people were asking God to come again and they were about to give up when He came in Glory. “So here with us, in such straits, on the brink of despair, with the door shut on every hope of success, God Himself entered into our midst.” Unfortunately the majority of information we have on Rowland and these times comes from Harris’ journal, so in the seven years he was away we do not have a lot of evidence on the state of spiritual affairs during this period. The little we do have seems to show that times were still really good, so I find it difficult to understand William’s situation unless things had been quiet for a few years in his area.

Robert Jones recalls 1762, “There was a great difference between this revival and that which began at first through the agency of Mr Harris. The mode of proceeding in that was sharp and very thunderous; but in this, as in the house of Cornelius long ago, great crowds magnified God without being able to cease, but sometimes leaping in jubilation. Sometimes whole nights were spent with a voice of joy and praise, as a multitude that kept holy day. I heard from a godly old woman that it lasted three days and three nights without a break in a place called Lon-Fudr in Lleyn, one crowd following another. When some went home, others came in their place, and although they went to their homes for a while, they could stay there hardly any time before returning.”

Harris heard in February 1763, “the spirit of singing that is fallen on many parts, and of several hundred awakened in Cardigan, Carmarthen and other shires.” In May he witnessed up to 12,000 coming to hear the Word. As usual criticism followed the revival and newspapers could be accused of distorting, caricaturing and even fabricating the facts. People forget that God moves in different ways and the manifestations of one revival will be very different from another. This revival was occasioned by singing, dancing and jumping and of course this offended some people and as usual the offended do not take time to discern if this is the work of Holy Spirit or not. As mentioned above the flesh gets into these manifestations from time to time and so discernment if probably one of the most important gifts you can have at the time of revival.

For Rowland, with the blessings of revival came further persecution from the bishop in 1763 when a William Williams was appointed to the curacies of Llangeitho and Nantcwnlle; Rowland was out of a job! Rowland carried out services at a house nearby and virtually all his congregation went with him; to such an extent that Holy Communion was not administered at the church for nearly 50 years. A chapel was built for Rowland at the nearby Gwynfil. In 1767 the church wardens and principal inhabitants of Nantcwnlle, together with the non-resident vicar asked Rowland to serve as curate again; to which he assented on the understanding that the bishop agreed, but the bishop did not agree. In 1769 he was offered the living of Newport in Pembrokeshire on the understanding that he would live there. However, “when the people around Llangeitho heard of it, they were greatly distressed. They flocked in great numbers to his house, and their entreaties, their importunities, and their weeping, were such as can hardly be conceived.” The living must have been very tempting, but he declined it. John Thornton, who had offered the living, wrote to Rowland’s son, Nathaniel, “I had a high opinion of your father before, but I have now a still higher opinion of him, though he declines to accept my offer. The reasons he assigns are highly creditable to him. It is not a usual thing with me to allow other people to go to my pocket, but tell your father, that he is fully welcome to do so whenever he pleases.”

Despite the evil intentions of the bishop, Rowland’s work was not curtailed in the slightest. In 1764 Rowland made a defence to the Bishop on the revival. This was rejected on the grounds that it estranged people from the Established Church and belittled the clergy! Rowland had the continuing help of William Williams who assisted at Llangeitho and travelled all over Wales. Howel Davies was still in the field as was Peter Williams who travelled in England and Wales. New boys coming up were Rowland’s son, Nathaniel and David Jones of Llan-gan who travelled extensively in North Wales. Llan-gan became a centre for Methodism in Glamorgan. One witness said, “The travellers increased all the way as we went until we arrived at Llan-gan, about eleven miles distant; and many coming from a greater distance overtook us on the road. Such was our desire for spiritual food, that we could not be prevented by any weather, however severe.” Jones was very meek in spirit, the opposite of Nathaniel Rowland who was proud and domineering and lived on his father’s prestige.

In 1770 George Whitefield and Howel Davies died, to be followed in 1773 by Howel Harris. In 1773 Rowland was used to convert Thomas Charles who later was so much involved with education. Charles would come to Llangeitho twice a year during his holidays, to sit under Rowland. Rowland began to associate himself with the great supporter of Methodism, the Countess of Huntingdon. He visited England to preach for her from time to time and she got him the position of Chaplain to the Duke of Leinster; that gave him some money and the opportunity to preach to some exalted people. He went around consecrating several new church buildings in North as well as South Wales.

In his final year Rowland was still very busy and was able to enjoy the revivals that popped up from time to time. In 1772 there was a blessing in the Caerphilly area and in 1779 something began in the mountains near Llangeitho. A report said, “Daniel Rowland heard the glad tidings, and he resolved to ascend the mountain to see this thing which the Lord had wrought. He preached, the power was still present, and even mightier than on the preceding Sabbath. On his return home he said to his friends, ‘It is a heath fire and will spread abroad.’ And it did spread from these dreary mountains to the valleys and plains around, until it had reached many and far-distant localities in South and North Wales, and thousands were brought earnestly to seek everlasting life.” In 1789 it was Dafydd Morris who was God’s instrument of revival in the Llanwrtyd area of Breconshire.

Rowland’s ministry was as powerful as ever and the years 1780-1 were particularly fruitful in South Wales, the blessing radiating from Llangeitho. Nathaniel reported that it began when he was preaching on Matthew 11:25-26. “The entire chapel seemed as if it was filled with some supernatural element, and the whole assembly was seized with extraordinary emotions.” The monthly sacrament had thousands attending; people came from up to 80 miles away and many came on foot. Rowland would observe them coming and say, “Well, here they come, bringing heaven along with them.” In 1781 the fires started in Bala and in 1785 there were similar scenes in Caernarvonshire. William Williams reported a revival in 1789-91.

Over one hundred preachers in Wales thought of Rowland as their father and they would normally meet him for counsel around four times a year. A witness wrote that around 14,000 came to hear him preach on Sacrament Sunday; the chapel held over 3,000 and with four clergymen administering it would still take over an hour for the less ‘pushy’ to get to the Communion Table. William Romaine, the evangelical, met Rowland in a bookshop, probably in Bristol. He said, “What, do you, the most eminent divine, come here to buy books? I thought you had the Spirit of God to study His Word and compose your sermon!” According to Edward Morgan, “Rowland used to say in his last days, that he had been endeavouring to learn four lessons all the time he was in the vineyard and service of the Lord, but notwithstanding that he was a very imperfect scholar in his old age. They were the following truths: To repent without despairing; to believe without presuming; to rejoice without levity; to be angry without sinning.”

In the year of his death he was preaching as clearly, as lively, as powerfully and with as much authority as ever. He had very good health and it was only when he got into his seventies that there was any cause for concern. Two Sundays before his death he said to his church, “I am almost leaving, and am on the point of being taken from you. I am not tired of the work, but in it. I have some presentiment that my heavenly Father will soon release me from my labours, and bring me to my everlasting rest. But I hope He will continue His gracious presence with you after I am gone.” Lady Huntingdon arranged for a miniature to be painted of Rowland and it was finished just a week before he died on 16 October 1790. He only felt unwell for three days before he died. He was buried in Llangeitho churchyard and the funeral sermons were made by David Jones and John Williams.

Daniel Rowland led revival for 55 years; what an honour, what a joy! He may have been the greatest preacher these Islands have ever heard. He led the Methodists in Wales from birth through to maturity. He was loved and respected by thousands. Not a bad memorial!

This essay has been taken entirely from ‘Daniel Rowland and the Great Evangelical Awakening in Wales’ by Eifion Evans, published by The Banner of Truth Trust 1985. Mr Evans has written several books on Welsh Spiritual Heritage.

‘Howel Harris’ on this website is very similar to this essay and is taken largely from the same book. Their lives were so intertwined that large parts are the same. There are also considerable similarities in parts of ‘Revivals – Wales’, also on this website.

There are very few sources available to do a biography on Rowland. Soon after his death Lady Huntingdon asked his family to collect together all the information on Rowland and send it to her so that a biography could be written. Sadly she died before she could organise this and tragically all the documents disappeared.