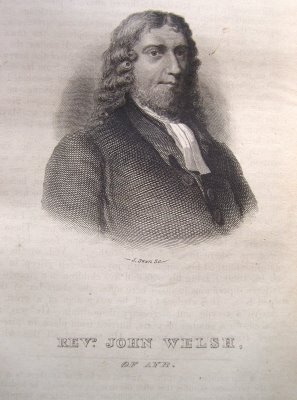

John Welch

John Welch or Welsh (1568?-1622)

Intercessor, Evangelist, Preacher, Minister

John Welch (alternative spelling Welsh) was born a little before 1570 and was a gentleman by birth, his father being Laird of Colliston, Dunscore Parish in Nithsdale, an estate rather moderate in size. He did not make a very encouraging start to life. He often ran away from school and after he had passed through grammar school he left his father’s house, joining the thieves on the English border who lived by stealing from both those in England and Scotland. Then, when he was clothed only with rags, the prodigal’s misery brought him to the prodigal’s resolution; so he resolved to return to his father’s house, but did not dare do this until he could find an intermediary who could help in the reconciliation.

On his way home he went to Dumfries, where he had an aunt, Mrs Agnes Forsyth; and with her he spent a few days, trying to persuade her to help with the reconciliation to his father. While staying with her, his father fortuitously came to visit Mrs Forsyth. After they had talked a while, she asked him whether he had ever heard any news of his son John. He replied with great grief, ‘O cruel woman, how can you name him to me! The first news I expect to hear of him is that he is hanged for a thief.’ She answered that many a dissolute boy had become a virtuous man and comforted him. He maintained his grievance, but asked whether she knew if his lost son was still alive. She answered yes, he was, and she hoped he should prove a better man than he was a boy, and with that she called upon John to come to his father. He came weeping, and kneeled begging his father, for Christ’s sake, to pardon his bad behaviour, and promised to be a new man. His father reproached and threatened him, yet in the end, by his tears and Mrs Forsyth’s persistence, he was persuaded to be reconciled. The boy entreated his father to send him to college and there test his behaviour; saying that his father should disown him forever if he ever went back to his old ways. So his father took him home, and put him in the new Edinburgh University (graduated August 1588). There he became a diligent student with great expectations; showing himself a sincere convert; he went into the ministry. (He was much younger than most which shows what a brilliant student he must have been).

His first appointment was at Selkirk (1589) where the parish was very godless. There were very few Reformed ministers at the time, so most had to look after several parishes. Welch looked after St Marie Kirk, New Kirk of Ettrick, Eankilbum, and Ashkirk. Many who lived in his parishes and some of the neighbouring ministers, would have been happy to see Papism return, so he had little support. Nevertheless, Welch preached every day, going around his parishes, gathering those who were prepared to listen. Some of the ministers of that area were more ready to pick a quarrel with him than to follow his doctrine, as was shown in the records of the Synod - many censures are recorded and few defended him. Yet it was thought his ministry there was not without fruit. Being a young unmarried man, he boarded in the house of a landowner named Mitchelhill, who was also a reformed man. A boy who was living there retained a respect for John Welch and his ministry his whole life. His custom was, when he went to bed at night, to lay a Scots plaid on his bed-clothes, and when he went to his night-prayers, to sit up and cover himself with it. From the beginning of his ministry to his death, Welch considered the day ill-spent if he was not in prayer for at least one third of his time.

An old man called Ewart, who remembered Welch, said, ‘He was a type of Christ;’ an expression more significant than proper. He meant that he was a man who imitated Christ, as indeed in many things he did. He also said that Welch used to preach publicly once every day, and spend his whole time in spiritual exercises; that some in that place looked on his ministry with great tenderness, but that he was forced to leave because of the ill will of his opponents.

The main reason for him leaving was a profane gentleman from the area, Scot of Headschaw. Either because Welch had reprimanded him, or merely because of hatred, he was most unjustifiably abused by this man. One of the attacks on Welch was as follows. Welch always kept two good horses for his own use, and Scot, when he could do no more, either with his own hand or by his servants, cut off the hind quarters’ of the two innocent beasts, as a result they both died. Such a vile attack as this persuaded Welch to listen to a call to the ministry at Kirkcudbright, which became his next post.

He stayed at Kirkcudbright (a hotbed of Catholicism - the previous minister and a neighbouring minister were assassinated; Welch’s appointment to such a difficult place shows in what high esteem he was held) from 1595 to 1600. He reaped a harvest of converts there; converts who continued long after he left the parish; they became a part of Samuel Rutherford’s congregation. Despite his success there, the people of the parish of Kirkcudbright never tried to detain him when he was asked to take the position of minister at Ayr.

He married Elizabeth Knox (before 1596), daughter of the famous John Knox, minister at Edinburgh. They were married until his death and had three sons. The first was called Dr Welch, a doctor of medicine, who was sadly killed through an innocent mistake in the Low Countries. Another son was most tragically lost at sea. His ship sank and he swam to a rock in the water, but starved there as he had no provisions. When his body was found sometime later, he was kneeling with his hands outstretched. His friends and the world could take some consolation in this, despite his dreadful death. Their third son, Josias Welch, inherited his father’s gifts. He became the minister at Temple-Patrick in the north of Ireland, and was commonly called the Cock of the Conscience by the people of that country because of his extraordinary awakening and rousing gift. He died young, leaving a son, John Welch, the minister of Irongray in Galloway.

While Welch was at Kirkcudbright, he met a young gentleman in scarlet and silver lace, called Robert Glendinning, who was recently home from his travels. He much surprised the young man by telling him that he needed to change his clothes and way of life and that he must start studying the Bible. Welch realised that Glendinning was going to be his successor in the ministry at Kirkcudbright, which duly came about.

In December 1597 he was asked to speak to a gathering of ministers in Edinburgh. An erroneous report was read to the Privy Council which reported that he had said his Majesty was possessed with a devil and after the deliverance of that devil there joined to his Highness seven devils, which were his Majesty's Council. As a result of this he was summoned before the Council, but Welch thought it wiser to disappear for a while as he was fairly sure that he would get no justice from that Council. He was told he could not preach anymore; it was six months before this punishment was withdrawn.

John Welch was promoted to the parish of Ayr in 1600, and there he stayed until he was banished. He had a very hard beginning, but a very sweet end. When he first came to the town, the country was so wicked and the hatred of godliness so great that there was nobody in the whole town who would give him accommodation. Eventually, he was able to stay in part of the house of John Stuart, who was a gentleman, merchant, sometime provost of Ayr, an eminent Christian and great assistant to Welch. When he first took up his residence in Ayr the place was so divided into factions and filled with bloody conflicts that a man could hardly walk the streets in safety. Since duels were commonplace, Welch made it his first job to eradicate the bloody quarrellings, but found it very difficult work. He was so eager to pursue his purpose that he would often rush between two parties of men fighting, even amongst the blood and the wounds. He used to cover his head with a head-piece before he went to separate these bloody enemies, but would never use a sword, so they might see that he had peaceful intentions. Little by little he made the town a peaceful place. After he had ended a skirmish amongst his neighbours and reconciled them, he used to set up a table in the street to bring the enemies together. Beginning with prayer, he persuaded them to declare that they were friends and to eat and drink together; then he ended by singing a psalm. After the people began to notice what Welch was doing, and after listening to his heavenly doctrine, they quickly came to respect him; he became not only a necessary counsellor, without whose advice they would not do anything, but also an example to imitate.

Welch gave himself wholly to ministerial exercises, preaching once every day; he prayed for a third of his time, and was unwearied in his studies. For a proof of this, it was found among his papers that he had abridged Suarez’s metaphysics as soon as he received it, and he was fairly old at the time. All this shows that he was a man of great diligence, but also of a strong and robust natural constitution, otherwise he had never coped with all the work.

Sometimes, before he went to preach, he would send for his elders and tell them he was afraid to go to the pulpit, because he found himself empty; he would therefore ask one or more of them to pray, and then he would get into the pulpit. But it was observed that this humble exercise was usually followed by a flame of extraordinary power. He would often retire to the church of Ayr, which was some distance from the town, and there spend the whole night in prayer; and he prayed not only with an audible, but sometimes a loud voice. He was a man who had discovered that there was no point ministering if God was not with him. He pressed into God through prayer, because he wanted to have an intimate relationship with the Lord, and out of that would come manifestation of His power and glory.

Welch had come to Ayr to help the elderly and sickening minister called Porterfield. He was judged no bad man for his personal inclinations, but he was too easy going. He joined in with his neighbours in their pursuits, such as archery on Sunday afternoons, to Welch’s great dissatisfaction. Welch, together with John Stuart and Hugh Kennedy, two intimate friends, used to spend Sunday afternoon in religious conference and prayer. To this exercise they invited Porterfield, which he could not refuse; by which means he was not only diverted from his former sinful practices, but also brought to a more watchful and edifying behaviour.

While Welch was at Ayr, the Lord’s Day was not respected at a gentleman’s house about eight miles away, by reason of a great number of people playing football, and other pastimes. After writing several times to him to suppress the disrepect of the Lord’s Day at his house - which he slighted, not wanting to be called a puritan - Welch came one day to his gate, and told him that he had a message from God to tell him. Because he had ignored the advice given him from the Lord, and would not stop profaning the Lord’s Day, therefore the Lord would cast him out of his house and none of his children should enjoy it. This accordingly came to pass; for although he was prosperous at this time, later everything went against him until he was obliged to sell his estate; and when giving the purchaser possession of it, he told his wife and children that he had realised Welch was a true prophet.

As the gift in which John Welch excelled at most was prayer, so his greatest attainments were related. He used to say he wondered how a Christian could lie in bed all night, and not get up to pray. Many times he got up, and many times he watched. One night he got out of bed and went into the next room, where he stayed so long at secret prayer, that his wife, fearing he might catch cold, decided to get up and follow him. As she listened, she heard him speak as if by interrupted sentences, ‘Lord, wilt Thou not grant me Scotland?’ and, after a pause, ‘Enough, Lord, enough.’ She asked him afterwards what he meant by saying, ‘Enough, Lord, enough?’ Though he did not like her curiosity, he told her that he had been wrestling with the Lord for Scotland, and found there was a sad time at hand, but that the Lord would be gracious to a remnant. He would have been talking about the imposition of Episcopacy that was soon going to push back the Reformation.

An honest minister, who was a parishioner of Welch’s for a long time, wrote that one night as Welch watched in his garden very late, some of his friends were waiting for him in his house. Tired of waiting, one of them opened a window facing the place where Welch was, saw clearly a strange light surround him, and heard him speak strange words about his spiritual joy.

John Welch, on account of his holiness, abilities and success, had acquired among his subdued people a very great respect, yet this was to grow even more after the great plague which raged in Scotland in his time. The magistrates of Ayr decided to guard the ports with sentinels and watchmen because the plague was raging in much of Scotland, but it had not reached the walled city of Ayr. One day two travelling merchants, each with a pack of cloth upon a horse, came to the town desiring entrance so they might sell their goods. They produced a pass from the magistrates of the town from where they had come, which was at that time free from the plague. Notwithstanding all this, the sentinels stopped them till the magistrates were called. They would do nothing without their minister’s advice, so John Welch was called, and his opinion asked. Taking off his hat he looked up towards heaven. After a short space of time he told the magistrates that they would do well to discharge these travellers from their town, affirming that the plague was in the packs of cloth. So the magistrates commanded them to be gone. They went to Cumnock, a town about twenty miles away, and there sold their goods, creating such an infection in that place that the living were hardly able to bury their dead. This made the people begin to think of Welch as an oracle. Yet, though he walked with God and kept close with Him, he did not forget man. He frequently used to dine out with such of his friends as he thought were persons he might fellowship with. Once a year he would invite all his close friends in the town to a party in his house, where there was a banquet of holiness and sobriety.

Welch was so successful at Ayr that in March 1603 the Town Council voted to build a bigger church through public subscription. Sadly, Welch had to leave the parish before this plan could be carried out. In April 1604 Porterfield, the official pastor of the parish finally died and Welch was appointed in his place. The success of his ministry in Ayr can be gleaned from a letter he wrote from France referring to his time at Ayr, ‘I had my choice of many hundreds, unto whom I might have been bold to communicate both the desolations and comforts of my soul.’ At the time Ayr had a population of 3,000, so having many hundreds who he considered strong Christians shows that a large part of the parish had turned to the Lord.

He continued the course of his ministry in Ayr until king James’s purpose of destroying the Church of Scotland, by establishing bishops, was clear. Then it became his duty to edify the Church by his sufferings, as formerly he had done by his doctrine. He had spoken out several times against the idea of Episcopacy, believing it to be a great evil and he would stand against it again. Most of the chief ministers of the day held the same view.

The reason why James VI was so set on bishops was neither their divine institution which he denied they had, nor the profit the Church would gain from them, for he knew well both the men and their communications, but merely because he believed they were useful instruments to turn a limited monarchy into absolute dominion, and subjects into slaves. Always in the pursuit of his design, he resolved first to destroy General Assemblies, knowing well that so long as assemblies met freely, bishops could never get their designed authority in Scotland.

The General Assembly at Holyrood house in 1602, with the king’s consent, appointed their next meeting to be held at Aberdeen, on the last Tuesday of July 1604; but before that day came, the king, by his commissioner, the laird of Laurieston, and Mr Patrick Galloway, moderator of the last General Assembly, in a letter directed to the several presbyteries, prorogued the meeting till the first Tuesday of July 1605, at the same place. In June 1605 the expected meeting, was, by a new letter from the king’s commissioner, and the commissioners of the General Assembly, absolutely discharged and prohibited, but without naming any day or place for another assembly. So the series of our assemblies ended, never to start again in the same format until the Covenant was renewed in 1638. However, many of the godly ministers of Scotland knew well that if once the hedge between the government and the Church was broken, then corruption of doctrine would soon follow. They resolved not to quit their assemblies, and therefore a number of them convened at Aberdeen on July 2nd, 1605, being the last day that was distinctly appointed by authority. When they met they did no more but constitute themselves, then dissolve the meeting. Amongst these ministers was John Welch (he arrived on the 4th, those from the south were asked three days later than those from the north), who, though he had not been present upon that precise day, yet, because he came to the place and made a point of approving of what his brethren had done, was accused as guilty of the treasonable act committed by them.

Within a month of this meeting many of these godly men were incarcerated, some in one prison, some in another. Welch was sent to Edinburgh Tolbooth, and then to Blackness; and so from prison to prison, until he was banished to France, never to see Scotland again.

Now the scene of Welch’s life begins to alter; but before his sufferings he had a strange warning. After the meeting at Aberdeen was over, he retired immediately to Ayr. One night he got up, went into his garden, as was his custom, but stayed longer than usual, which worried his wife. When he returned she told him off for staying out so long on account of his health. He asked her to be quiet.He told her that they would be all right, but he knew well that he would never preach again in Ayr; and accordingly, before the next Sunday he was carried to Blackness Castle a prisoner. After this he, along with many others who had met at Aberdeen, were brought before the Council of Scotland at Edinburgh to answer for their rebellion and contempt in holding a General Assembly not authorised by the king. Because they refused to recognise the authority of the secret council over spiritual matters, such as the nature and constitution of a General Assembly, they were first remitted to the prison at Blackness, and then other places. Six of the most important of them were brought at night from Blackness to Linlithgow to stand before the criminal judges to answer an accusation of high treason.They were condemned by the verdict of a jury of very considerable gentlemen, as guilty of high treason, the punishment being deferred till the king’s pleasure should be known. Their punishment was banishment. While he was in Blackness, Welch wrote his famous letter to Lilias Graham, Countess of Wigton, in which he mentions in the strongest terms, his consolation in suffering, his desire to be dissolved that he might be with the Lord and the judgments he foresaw coming on Scotland.He wrote:

‘Who am I, that He should first have called me, and then constituted me a minister of the glad tidings of the Gospel of salvation these years already, and now, last of all, to be a sufferer for His cause and kingdom. Now, let it be so that I have fought my fight, and run my race, and now from henceforth is laid up for me that crown of righteousness, which the Lord, that righteous God, will give; and not to me only, but to all that love His appearance, and choose to witness this, that Jesus Christ is the King of saints, and that His Church is a most free kingdom, yea, as free as any kingdom under heaven, not only to convocate, hold, and keep her meetings, and conventions, and assemblies; but also to judge all her affairs, in all her meetings and conventions, amongst her members and subjects. These two points: (1.) That Christ is the head of His Church; (2.) That she is free in her government from all other jurisdiction except Christ’s; these two points, I say, are the special cause of our imprisonment being now convicted as traitors for the maintaining thereof. We have been ever waiting with joyfulness to give the last testimony of our blood in confirmation thereof, if it should please our God to be so favourable as to honour us with that dignity; yea, I do affirm, that these two points above written, and all other things which belong to Christ’s crown, sceptre, and kingdom, are not subject, nor cannot be, to any other authority, but to His own altogether. So that I would be most glad to be offered up as a sacrifice for so glorious a truth: it would be to me the most glorious day, and the gladdest hour I ever saw in this life; but I am in His hand, to do with me whatsoever shall please His Majesty.

I am also bound and sworn, by a special covenant, to maintain the doctrine and discipline thereof, according to my vocation and power, all the days of my life, under all the pains contained in the book of God, and danger of body and soul, in the day of God’s fearful judgment; and therefore, though I should perish in the cause, yet will I speak for it, and to my power defend it, according to my vocation.’

He wrote about the same time to Sir William Livingstone of Kilsyth.

‘As for that instrument, Spottiswoode, we are sure the Lord will never bless that man, but a malediction lies upon him, and shall accompany all his doings; and it may be, sir, your eyes shall see as great confusion covering him, ere he go to his grave, as ever did his predecessors. Now, surely, sir, I am far from bitterness, but here I denounce the wrath of an everlasting God against him, which assuredly shall fall, except it be prevented. Sir, Dagon shall not stand before the ark of the Lord, and these names of blasphemy that he wears, of Arch and Lord Bishop, will have a fearful end. Not one beck is to be given to Haman, suppose he were as great a courtier as ever he was. Suppose the decree was given out, and sealed with the king’s ring, deliverance will come to us elsewhere and not by him, who has been so sore an instrument; not against our persons; that were nothing, for I protest to you, sir, in the sight of God, I forgive him all the evil he has done, or can do, to me; but unto Christ’s poor Kirk, in stamping under-foot so glorious a kingdom and beauty as was once in this land. He has helped to cut Sampson’s hair and to expose him to mocking; but the Lord will not be mocked. He shall be cast away as a stone out of a sling, his name shall rot, and a malediction shall fall upon his posterity, after he is gone. Let this, sir, be a monument of it that it was told before, that when it shall come to pass, it may be seen there was warning given him; and therefore, sir, seeing I have not the access myself, if it would please God to move you, I wish you would deliver this hand-message to him, not as from me, but from the Lord.’

The man of whom he complains, and threatens so sore, was John Spottiswoode, at that time archbishop of Glasgow; and this prophecy was literally accomplished, though after the space of forty years. For, first the archbishop himself died in a strange land, and, as many say, in misery. Next, his son Robert Spottiswoode, sometime President of Session, was beheaded by the Parliament of Scotland at the market-cross of St Andrews in the winter after the battle of Philiphaugh. As soon as he came upon the scaffold, Mr Blair, the minister of the town, told him that now Welch’s prophecy was fulfilled upon him; to which he replied in anger, that Welch and he were both false prophets.

Lord Ochiltree, the Governor of the Castle, being both son to the good Lord Ochiltree, and Mr Welch’s uncle-in-law, was indeed very civil to him. Being for a long time, through the multitude of affairs, kept from visiting Welch, as he was one day walking in the court, and espying him at his chamber-window, he asked him kindly how he did, and if in anything he could serve him? Welch answered, that he would earnestly entreat his Lordship, being at that time about to go to Court, to petition king James in his name that he might have liberty to preach the Gospel; which my Lord promised to do. Mr Welch then said, ‘My Lord, both because you are my kinsman, and for other reasons, I would earnestly entreat you not to promise, except you faithfully perform.’ His Lordship answered he would faithfully perform his promise, and so went to London. Though at his arrival he really purposed to present the petition to the king, he found the King in such a rage against the godly ministers that he durst not at that time present it; so he thought fit to delay, and thereafter entirely forgot it.

The first time that Welch saw his face after his return from Court, he asked him what he had done with his petition. His Lordship said that he had presented it to the king, but that the king was in so great a rage against the ministers at that time, he believed it had been forgotten, for he had got no answer. ‘Nay,’ said Welch to him, ‘my Lord, you should not lie to God, and to me; for I know you never delivered it, though I warned you to take heed not to undertake it except you would perform it; but because you have dealt so unfaithfully, remember God shall take from you both estate and honours, and give them to your neighbour in your own time.’ This accordingly came to pass, for both his estate and honours were in his own time translated to James Stuart, son of Captain James, who was a cadet, but not the lineal heir of the family.

Now the time had come when John Welch must leave Scotland, never to see it again. Upon the 7th of November 1606, he with his neighbours took ship at Leith; and though it was but two o’clock in the morning, many were waiting with their afflicted families, to bid them farewell. With Mr Welch, five other godly ministers were banished for the same cause: John Forbes, who went to Middleburgh to the English chapel there; Robert Dury, who went to Holland and was minister to the Scots congregation in Leyden; John Sharp, who became minister and Professor of Divinity at Die in the Dauphinate, where he wrote “Carfus Theologicus,” etc; and Andrew Duncan and Alexander Strachan, who, in about a year, got liberty to return unto their former places. After prayer, they sung the 23rd Psalm, and so, to the great grief of the spectators, set sail for the south of France and landed in the river of Bordeaux. France, at this time, had a large number of Reformed churches, but the Protestants had recently experienced severe persecution and were about to experience more. In the end Protestantism was virtually wiped out in France.

Welch was offered the Theology chair at Dijon University, but due to his ill health which was as a result of his imprisonment, and the need to stay on the coast for when his family joined him, he turned the offer down. Within fourteen weeks after his arrival, such was the Lord’s blessing upon his diligence that Welch was able to preach in French. Accordingly, he was speedily called to the ministry; firstly, as a temporary measure (which lasted until 1614) in a village called Jonsac (this was a very uncomfortable place for Welch and his health suffered considerably); then Nerac; and lastly, from 1617 in St Jean d’Angely, an important Protestant walled town, where he continued the rest of the time he sojourned in France.

When he began to preach, it was observed by some of his hearers, that while he continued in the doctrinal part of his sermon, he spoke very correct French; but when he came to his application, and when his affections kindled, his fervour made him sometimes neglect the accuracy of the French construction. There were godly young men who admonished him of this, which he took in very good part. For preventing mistakes of that kind, he desired them, when they perceived him beginning to decline, to give him a sign by standing up. Thereafter, he was more exact in his expression through the whole sermon. So desirous was he, not only to deliver good matter, but to recommend it by neat expression.

There were frequently persons of great quality in his auditory, before whom he was just as bold as ever he had been in any Scottish village. This moved Mr Boyd of Trochrig once to ask him, after he had preached before the University of Saumur with boldness and authority as if he had been before the meanest congregation, how he could be so confident among strangers and persons of such quality. He answered he was so filled with the dread of God, that he had no apprehensions for man at all. ‘This answer,’ said Mr Boyd, ‘did not remove my admiration, but rather increased it.’

There was in his house, amongst many others who boarded with him for good education, a young gentleman of great quality and suitable expectations, the heir of Lord Ochiltree, Governor of the Castle of Edinburgh. This young nobleman, after he had gained very much upon Mr Welch’s affections, fell ill of a grievous sickness. After he had been long wasted by it, closed his eyes and expired, to the apprehension of all spectators; and was therefore taken out of his bed, and laid on a pallet on the door, that his body might be more conveniently dressed. This was to Mr Welch a very great grief, and he stayed with the body fully three hours, lamenting over him with great tenderness. After twelve hours, the friends brought in a coffin, whereinto they desired the corpse to be put, as the custom was. Mr Welch desired that, for the satisfaction of his affections, they would forbear for a time; which they granted, and returned not till twenty-four hours after his death. Then they desired with great importunity that the corpse might be coffined and speedily buried, the weather being extremely hot. Yet he persisted in his request, earnestly begging them to excuse him once more, so they left the corpse upon the pallet for a full thirty-six hours. Even after all that, though he was urged not only with great earnestness, but displeasure, they were constrained to forbear for twelve hours more. After forty-eight hours were past, Mr Welch still held out against them. Then his friends, perceiving that he believed the young man was not really dead, but under some apoplectic fit, proposed to him for his satisfaction, that trial should be made upon the body by doctors and surgeons, if possibly any spark of life might be found; and with this he was content. So the physicians were set to work, who pinched him with pinchers in the fleshy parts of his body and twisted a bow-string about his head with great force; but no sign of life appearing in him, the physicians pronounced him stark dead, and then there was no more delay to be made. Yet Mr Welch begged of them once more that they would but step into the next room for an hour or two, and leave him with the dead youth; and this they granted.

Then Mr Welch fell down before the pallet and cried to the Lord with all his might. He sometimes looked upon the dead body, continuing to wrestle with the Lord, till at length the dead youth opened his eyes and cried out to Mr Welch, whom he distinctly knew, ‘O sir, I am all whole, but my head and legs’ (these were the places they had sorely hurt with their pinching). When Mr Welch perceived this, he called upon his friends and showed them the dead young man restored to life again, to their great astonishment. (This story is somewhat questionable in its detail, although the core of it is probably true.)

While Mr Welch was ministering in one of these French villages upon an evening, a certain Popish friar travelling through the country because he could not find a lodging in the whole village, addressed himself to Mr Welch’s house for one night. The servants acquainted their master with the request and he was content to receive the guest. The family had supped before he came, so the servants conveyed the friar to his chamber; and after they had made his supper, they left him to his rest. There was but a timber partition betwixt him and Mr Welch; after the friar had slept his first sleep, he was surprised with the hearing of a silent but constant whispering noise, which troubled him.

The next morning the friar walked in the fields, where he chanced to meet with a country man, who, saluting him because of his habit, asked him where he had lodged that night? The friar answered he had lodged with the Huguenot minister. Then the countryman asked him, what entertainment he had? The friar answered, ‘Very bad;’ for, said he, ‘I always held that devils haunted these ministers’ houses, and I am persuaded there was one with me this night, for I heard a continual whisper all the night over, which I believe was no other thing than the minister and the devil conversing together.’ The countryman told him he was much mistaken, and that it was nothing else than the minister at his night prayer. ‘O,’ said the friar, ‘does the minister pray?’ ‘Yes, more than any man in France,’ answered the countryman; ‘and if you please to stay another night with him you may be satisfied.’ The friar got home to Mr Welch’s house, and pretending indisposition, entreated another night’s lodging, which was granted him.

Before dinner Mr Welch came from his chamber and made his family exercise, according to his custom. And first he sung a psalm, then read a portion of Scripture, and discoursed upon it; thereafter he prayed with great fervour, to all which the friar was an astonished witness. After exercise they went to dinner, where the friar was very civilly entertained, Mr Welch forbearing all question and dispute with him for the time. When the evening came, Mr Welch made exercise as he had done in the morning, which occasioned more wonder to the friar, and after supper they went to bed. But the friar longed much to know what the night-whisper was, and therein he was soon satisfied; for after Mr Welch’s first sleep, the noise began. The friar resolved to be certain what it was, and to that end he crept silently to Mr Welch’s chamber door. There he heard not only the sound, but the words distinctly, and communications betwixt God and man such as he thought had not been in this world. The next morning, as soon as Mr Welch was ready, the friar came and confessed that he had lived in ignorance the whole of his life, but now he was resolved to adventure his soul with him; and thereupon declared himself a Protestant. Mr Welch welcomed and encouraged him, and he continued a Protestant to his death.

When Louis XIII of France made war upon his Protestant subjects because of their religion, the city of St Jean d’Angely was besieged by him with his whole army and brought into extreme danger. Mr Welch was minister of the city and mightily encouraged the citizens to hold out, assuring them that God would deliver them. In the time of the siege, a cannon-ball pierced the bed where he was lying; upon which he got up, but would not leave the room till he had, by solemn prayer, acknowledged his deliverance. During this siege the citizens made stout defence, till one of the King’s gunners planted a great gun so conveniently upon a rising ground that he could command the whole wall upon which they made their greatest defence. Upon this, they were constrained to forsake the wall in great terror, and though they had several guns planted upon the wall, no man durst undertake to manage them. This being told to Mr Welch, he encouraged them still to hold out; and running to the wall, found the Burgundian cannonier, near the wall. He entreated him to mount the wall, promising to assist in person. The cannonier told Mr Welch that they needed to dismount the gun upon the rising ground, else they were surely lost. Welch asked him to aim well, and he would serve him, and God would help them. The gunner began to work and Welch ran to fetch powder for a charge, but as he was returning, the king’s gunner fired his piece, which carried the ladle with the powder out of his hands. This did not discourage him, for, having left the ladle, he filled his hat with powder, wherewith the gunner dismounted the King’s gun at the first shot, and the citizens returned to their posts of defence. This discouraged the King so much that he sent to the citizens to offer them fair conditions that they should enjoy the liberty of their religion and their civil privileges, and their walls should not be demolished, the king only desiring that he might enter the city in a friendly manner with his servants. This the citizens thought fit to grant, and the King and a few more entered the city for a short time.

While the king was in the city, Welch preached as usual. This offended the French Court; and while he was at sermon, the king sent the duke d’Espernon to fetch him out of the pulpit into his presence. The duke went with his guard, and when he entered the church where he was preaching, Mr Welch commanded to make way, and to place a seat that the duke might hear the word of the Lord. The duke, instead of interrupting him, sat down and gravely heard the sermon to an end; then told Welch that he wished to go with him to the king, which he willingly did. When the duke returned, the King asked him why he brought not the minister with him and why he did not interrupt him? The duke answered, ‘Never man spake like this man,’ but that he had brought him along with him. Whereupon Mr Welch was called; and when he had entered the king’s presence, he kneeled and silently prayed for wisdom and assistance. Thereafter the king challenged him how he durst preach in that place, since it was against the laws of France that any man should preach within the verge of his court? Mr Welch answered, ‘Sire, if you did right, you would come and hear me preach, and make all France hear me likewise. For,’ said he, ‘I preach, that you must be saved by the death and merits of Jesus Christ, and not your own; and I preach, that as you are king of France, you are under the authority of no man on earth. Those men whom you hear, subject you to the Pope of Rome, which I will never do.’ The king replied, ‘Well, well, you shall be my minister,’ and, as some say, called him father, which is an honour bestowed upon few of the greatest prelates in France. However, he was favourably dismissed at that time, and the king also left the city in peace.

But within a short time thereafter, the war was renewed. Welch told the inhabitants of the city, that now their cup was full and they should no more escape. This accordingly came to pass, for the king took the town, but commanded Vitry, the captain of his guard, to enter and preserve his minister from all danger. Horses and wagons were provided to transport Mr Welch and his family to Rochelle, where he stayed for a time.

After his flock in France was scattered, Welch obtained liberty to go to England. His friends entreated James VI that he might have permission to return to Scotland because the physician declared there was no other method to preserve his life, but by the freedom he might have in his native air.

[The following incident is mentioned by Dr M’Crie in his biography of Knox: Mrs Welch, by means of some of her mother’s relations at court, obtained access to James VI and petitioned him to grant this liberty to her husband. The following singular conversation took place on that occasion. His Majesty asked who her father was. She replied, ‘Mr Knox.’ ‘Knox and Welch!’ exclaimed he, ‘the devil never made such a match as that.’ ‘It’s right like, sir,’ said she, ‘for we never speired his advice.’ He asked her how many children her father had left, and if they were lads or lasses. She said three, and they were all lasses. ‘God be thanked,’ cried James, lifting up both his hands; ‘for an’ they had been three lads, I had never bruiked my three kingdoms in peace.’ She again urged her request, that he would give her husband his native air. ‘Give him his native air!’ replied the king, ‘give him the devil!’ a morsel which James had often in his mouth. ‘Give that to your hungry courtiers,’ said she, offended at his profaneness. He told her at last, that if she would persuade her husband to submit to the bishops, he would allow him to return to Scotland. Mrs Welch, lifting up her apron and holding it towards the King, replied, in the true spirit of her father, ‘Please your Majesty, I’d rather keep his head there.’ -EDITOR]

James would never yield his consent, protesting that he would be unable to establish his beloved bishops in Scotland if Mr Welch were permitted to return thither, so he languished at London a considerable time. His disease was considered by some to have a tendency to leprosy; physicians said he had been poisoned. He suffered from an excessive languor, together with a great weakness in his knees caused by his continual kneeling at prayer. It came to pass, that though he was able to move his knees and walk, yet he was wholly insensible in them, and the flesh became hard like a sort of horn. But when, in the time of his weakness, he was desired to remit somewhat of his excessive labours, his answer was he had his life of God, and therefore it should be spent for Him.

His friends importuned James very much, that if he might not return to Scotland, at least he might have liberty to preach in London; which he would not grant till he heard all hopes of life were past, and then he allowed him liberty to preach, not fearing his activity. As soon as ever Welch heard he might preach, he greedily embraced this liberty; and having access to a lecturer’s pulpit, he went and preached both long and fervently. This was his last performance, for after he had ended his sermon he returned to his chamber, and within two hours, quietly, and without pain, resigned his spirit into his Master’s hands. He was buried near Bethlehem Cemetery in the parish of St Botolph, Bishopsgate after he had lived little more than fifty-two years.

During his sickness he was so filled and overcome with the sensible enjoyment of God that he was overheard to utter these words: ‘O Lord, hold Thy hand, it is enough; Thy servant is a clay vessel, and can hold no more.’ It is questionable as to whether his sowing in painfulness, or his harvest in success, was greatest; for if either his spiritual experiences in seeking the Lord, or his fruitfulness in converting souls be considered, they will be found unparalleled in Scotland. And, many years after his death, Mr David Dickson, at that time a flourishing minister at Irvine, was frequently heard to say, when people talked to him of the success of his ministry, that the grape gleanings in Ayr in Mr Welch’s time were far above the vintage of Irvine in his own.

John Welch, in his preaching, was spiritual and searching, his utterance tender and moving; he did not much insist upon scholastic purposes, and made no show of his learning. One of his hearers, who was afterwards minister at Muirkirk, in Kyle, used to say that no man could hear him and forbear weeping, his conveyance was so affecting. He never himself appeared in print, except in his dispute with Abbot Brown, wherein he makes it appear that his learning was not behind his other virtues; and in another treatise, called Dr Welch’s Armageddon, supposed to have been printed in France, wherein he gives his meditation upon the enemies of the Church and their destruction.

This essay on John Welch is largely from John Howie’s ‘Scots Worthies’, first published 1775; revised and enlarged 1781. I have made some adjustments which can be seen in brackets, and I have made some other changes and deletions. The original article can be seen at http://www.reformation-scotland.org.uk/scots-worthies/john-welch/. A full biography of his life can be found at, http://www.archive.org/stream/lifejohnwelshmi00andegoog Another good mini-biography can be found at http://www.puritansermons.com/banner/jnwelsh.htm