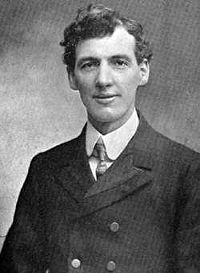

Evan Roberts

Evan Roberts (1878-1951) and the 1904 Revival

Intercessor and Revivalist

There is some contention as to how important Evan Roberts was to the 1904 Welsh Revival. It was the first revival where the newspapers played an important role. They seem to have focused on Roberts, and as a result, what was going on elsewhere in Wales tended to be ignored. It must be remembered that the Revival did not start with Evan Roberts and a great deal was going on in Wales at that time that had nothing to do with him. Having said that, I am going to focus this biography on Roberts, because by looking at his life we can get a good understanding of what happened in those heady days of 1904.

Roberts was born in Loughor, near Swansea, a town of around 2,000 people at the time. He was born on June 8th, 1878 in the family home called ‘Island House’. His father, Henry, was a collier. The one book Roberts read was the Bible, committing much of it to memory; at one time he memorised 174 verses in a week. His mother, Hannah, was a very moral person and, like her husband, a devout Christian. Roberts was baptised at Moriah Calvinist Methodist (now called Presbyterian) Chapel in Loughor.

When Roberts was eleven his father broke his leg and on recovering he could not walk very well, so he needed Roberts to help him with his work in the mine. Evan was eager to work and by the time he was sixteen he had been promoted to a responsible position at the coal face. Roberts was brought up by his parents to follow the ways of God. He earned good money, but was concerned that the money might draw him too far into the ‘world’. He was careful with his finances and was sure to tithe from them.

He loved his Bible and took it down the mine with him. One day he left it in the mine and there was an explosion. The pages of his Bible were scorched and scattered, but he gathered them up and took them home.

He worked in the mines until 1902. In September of that year Roberts gave up coal mining and became a blacksmith. He took up a three year apprenticeship with his uncle in Fforest, near Pontardulais, four miles from his home. All his free time was taken up with the Lord. He would read the Bible for hours, oblivious to the noises around him.

At the age of fifteen he was appointed a teacher over the local children and he continued to teach Sunday School for the next few years. For much of the time Roberts taught the children at the new Pisgah chapel and it was good training for the work that he was called to do later. He was clearly a bright, diligent and accomplished man. From joining the church membership at the age of thirteen, Roberts was seeking more and more of God. He himself considered these thirteen years before the revival began as a continuous preparation for the work that he was called to do. He did not find what he was looking for in the chapel services and he continued to search for the deeper things of God. He never had enough and was always pressing in for more. He said that nothing influenced him more than communion with God. He prayed from a very early age and as he got older he would pray at home, while walking along the road and often at work. He often preferred praying to having meals; he constantly felt something drawing him into communion with his Heavenly Father. He would often pray for hours at a time. The master at the school Robert’s attended at Newcastle Emlyn was amazed at the extraordinary intensity to his praying.

Around the age of eighteen, Roberts felt that he had some great purpose to achieve, but he did not know what it was or how the doors were going to open for him. He was often expectant of something happening to enable him to take the next step. During his apprenticeship he became more and more frustrated as his desire to serve God grew and grew in him. He had the desire inside him to preach and after repressing it for some time he wrote to a friend at the end of 1903 that he was going to give up his apprenticeship and start preaching. On December 13th he preached his first sermon at Moriah chapel. On December 31st he was given permission to start the process of becoming a minister. After a few months going around the district ‘on trial’, Roberts was accepted by the monthly meeting on May 25th.

He now had to pass the Provincial Exam that was to take place in August. Robert’s was concerned during the time of study for these exams, because more often than not he found the desire to pray stronger than the desire to study. However, he did manage to pass the exam. Next he had to decide whether to go forward for further study or begin preaching immediately. This decision involved quite a struggle, but he eventually decided to go to the Grammar School in Newcastle Emlyn to gain more knowledge to do his Master’s work. His tutor was John Phillips for the six weeks he was at the school. Phillips found his pupil to be of above average ability and was very impressed by him. However, Robert’s started to miss many of the lessons because he needed to pray and read the Bible.

At this point we have to leave the story of Evan Roberts because the first stirrings of the 1904 Welsh Revival are happening in New Quay, a port on the west coast of Wales. The minister at the Calvinistic Methodist chapel in New Quay was Joseph Jenkins. Jenkins was born in 1859 in the Rhondda and was brought up in a devout home. As a teenager he had been caught up by the evangelistic fervour of the Salvation Army. Having been a minister in Caerphilly and Liverpool, he came to New Quay in 1892.

By 1903 Jenkins, and his nephew John Thickens, who was minister at nearby Aberaeron, were very dissatisfied with the state of the church and their own ministries. They noticed a spiritual decline in the church, with people looking towards the ‘world’ to bring a ‘social Utopia’. In an attempt to reverse the decline, Jenkins and Thickens proposed to the presbytery (local ministers) that they put on a series of conferences on the theme of deepening the spiritual life. This was agreed and the first was at New Quay over the New Year. Thickens reported that during the conference there was an intense longing to know Christ’s love.

In February a young woman called Florrie Evans followed Jenkins home after a Sunday service. She said to him ‘…I saw the world in tonight’s sermon and I am under its feet; I cannot live like this.’ Jenkins told her to acknowledge the Lordship of Christ over her life. During a young people’s meeting the following Sunday, Florrie stood up and said ‘I love the Lord Jesus with all my heart’. An overpowering sense of God’s presence fell in the meeting and on subsequent meetings. Two other young women, Maud Davies and May Phillips were set on fire. The young people started to visit other churches to share the blessing. This could be said to be the beginning of the Welsh Revival of 1904. There may have been other similar happenings in other chapels in Wales at this time, but I have not found any recorded.

Another important link in the chain was Seth Joshua. Joshua was converted in a Salvation Army meeting and he immediately set about saving souls. He would go any place where the lost were and many came to the Lord through his ministry. He did mission after mission and on September 18th, 1904 he arrived at New Quay where he found ‘a remarkable revival spirit’. He was there for a week of remarkable meetings and around forty gave their lives to Jesus. He then left for his next mission in Newcastle Emlyn.

At the same school as Robert’s was his friend Sydney Evans, who was to play such an important role in the Revival. Evans went to Joshua’s meeting where he fell under severe conviction and after a battle he gave himself unreservedly to Christ. The meetings took two or three days to get going, but the breakthrough came and there was much blessing.

The next in the series of conferences organised by Jenkins was to begin in Blaenannerch, the Wednesday of Joshua’s meetings, and some of the students from Newcastle Emlyn, including Evan Roberts, went there. It was a two day meeting, with Joshua arriving early on the second day. The 7.00am service was closed by Seth Joshua praying, ‘Oh Lord do this, and this, and this, and bend us’ Roberts did not hear any of the words except ‘bend us’. On leaving the room he prayed that the Lord would bend them. Joshua was full of expectation going into the 9.00am meeting.

Roberts wrote, ‘I felt in going to the meeting that I was compelled to pray. When the meeting commenced many prayed, and I asked the Holy Spirit, “shall I pray now?” “No” said the Spirit in answer. Shortly some wonderful influence came over me. After many had prayed I felt some living energy or force entering my bosom, it held my breath, my legs trembled terribly; this living energy increased and increased as one after the other prayed until it nearly burst me, and as each finished I asked, “Shall I pray now?” When someone finished I prayed. My bosom boiled all through, and had it not been that I prayed, I would have burst. What boiled in my bosom? The verse, “for God commendeth His love.” I fell on my knees, with my arms outstretched on the seat before me, the perspiration poured down my face and my tears streamed quickly until I thought that the blood came out. Soon Mrs Davies, Mona, New Quay, came to wipe my perspiration, Magdalen Phillips stood on my right, and Maud Davies on my left. It was awful on me for about two minutes. I cried – “Bend me, bend me, bend me; Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh!” … What came to mind after this was, the bending in the day of judgement. Then I was filled with sympathy for the people who will have to bend in judgement day, and I wept. Afterwards, the salvation of souls weighed heavily on me. I felt on fire for going through the whole of Wales to tell the people about the Saviour.’ It was in this way that Roberts was filled with Holy Spirit and set on fire for Wales.

Jenkins and Thickens, who had organised the conference, were disturbed by Roberts’ outburst. They were looking for a deepening of spiritual life and such emotionalism as exhibited by Roberts was not something they welcomed. However, they soon realised that one could not control Holy Spirit and joined in the work.

The next few days were spent reading the Bible, praying and speaking in a few places. People from the places where Roberts spoke were impressed by him, particularly by the intensity of his prayers. His biographer D M Philips says, ‘I stated that his prayers, though silent, were extraordinary in power. Another thing that I wish to add in this connection is the hold that his prayer takes upon his whole body. In this, he is the most extraordinary person that I have ever seen. One would think that every word is the product of his whole being, body and souls. His sighs seem to rise from the depths of his spirit, and pass along every nerve. From this we can imagine how much agony of soul and physical effort an hour or two in a meeting cost him.’ Some thought that he was bordering on madness. His landladies were very concerned about his mental health and about his room-mate, Sidney Evans, for that matter. His friends were concerned that they could not bring him down to earth. His mind was always on heavenly matters. He recalled that he settled down one evening to study at 10.00pm and then remembered that he had not thanked God for something and the next thing he knew it was 11.00pm. He could not understand how he had lost an hour and the next thing he knew was that it was midnight and he had lost another hour.

There was an excellent meeting at Capel Drindod. It was led by Jenkins with several of the New Quay young women there. Roberts took part and there were many blessings. His friends had to almost drag him away from the meeting at about 11.30pm. They walked home, arriving there around 1.00am, but he did not sleep all night. It was at this time that he was wondering whether 100,000 souls were too many to ask of the Lord.

Roberts had been planning to take Sydney Evans and some of the New Quay women on an evangelistic tour of Wales. However, on Sunday, October 30th the Lord directed him to go home to Loughor to work with the young people. The Spirit so strongly brought the young people to his mind that he could not but obey. He decided to go home and lead nightly meetings for a week. The Sunday meetings were full of Holy Spirit and Roberts, as usual, was thinking all the time on heavenly matters. His friends were still concerned about his mental condition.

His time in Newcastle Emlyn had been crucial for Roberts. Although the things of God had dominated his daily life since he was thirteen, it was only at Blaenannerch that he had been filled with the Spirit. A revival atmosphere had been in Wales for around seven months and he was caught up in it. Holy Spirit used the few weeks Roberts had in Newcastle Emlyn to develop his spirit. He had visions, pictures, words, etc of instruction from the Spirit. He became spiritually discerning and familiar with the leading of the Spirit. All these things equipped him to lead the revival that would break out in Loughor on his return.

On his arrival in Loughor his family noticed the change in him, even the way he talked was different. His brother Dan told him that his eyes were very weak, but Evan prophesied that they would be healed and they were. He sat down at the organ and began to play, but he burst into tears and said ‘Dan, you shall see there will be a great change in Loughor in less than a fortnight. We are going to have the greatest Revival Wales has ever seen.’ He then got permission to hold his meetings and the first one, with seventeen young people, was held that night. Roberts told of what had been happening in New Quay and Newcastle Emlyn and asked them all to make a public confession of Christ. It was a hard meeting as the young people had to overcome their familiarity with Roberts and the traditions of the day. He pressed in and after a long time they each made a confession, including his brother and three sisters. It was noticed that he had changed, in that he used to be shy and nervous, but now he came to meetings with boldness and confidence. This victory, like most victories, did not come without contention. Satan invaded Roberts with doubts about his abilities and his right to lead the meetings.

The following day the meeting was at Pisgah where some of those at the meeting the previous night testified to how changed they felt after their public confession. The confession seems to have opened their hearts to the work of Holy Spirit. Six more made open confession that night. The meeting lasted three hours and consisted of confession, prayer and testimony. The training Roberts had received over the previous weeks bore fruit in these meetings, as he would only do what Holy Spirit was bidding. This was also a feature of the coming meetings.

The format of the meetings was a reading, a hymn, prayers and then Roberts would talk about ‘1. If there is sin or sins hitherto unconfessed, we cannot receive the Spirit. Therefore we must search and ask the Spirit to search. 2. If there is anything doubtful in our lives, it must be removed – anything we were uncertain about its rightness or wrongness. That thing must be removed. 3. An entire giving up of ourselves to the Spirit. We must speak and do all He requires of us. 4. Public confession of Christ.’

The meetings continued with some success and the word got around the neighbourhood that the Spirit was stirring. The meeting on Friday was the largest so far, with old as well as young and Baptists as wells as Congregationalists joining the Calvinistic Methodists. The meetings became a topic of conversation, with some criticising the new method, and some Roberts’ state of mind. The power of the Spirit in the meetings was becoming stronger and the Saturday meeting lasted for over five hours. Sixty confessed Christ at the Sunday meeting and it was here that he taught them the prayer ‘Send the Spirit now, for Jesus Christ’s sake.’

By November 7th, the start of the second week; people in the town were convinced that some irresistible power was gradually taking hold of the people. At 7.00pm there was a prayer meeting and the chapel was filled to bursting. After speaking on the last chapter of Malachi, Roberts asked some of those who had not made a public confession of Christ, to do so. After a number had complied with his request, nearly everyone was moved to tears and many cried loudly and wept in agony. ‘Those present this night have no doubt that they heard some powerful noise, and felt the place filled with the Divine Presence. The people one after the other fell in agony, because of their souls’ condition. …The next step is more wonderful still. Evan Roberts asked them to pray the “Direct Prayer,” as he calls it. “Send the Holy Spirit now, for Jesus Christ’s sake.” He prayed it firstly, then everyone in the meeting was to pray it in turn. When it was about half-way the second time, the whole audience gave way before some irresistible influence, and now the state of things is beyond any description.’ The meeting went on for eight hours.

The Tuesday meeting was very hard. Many left by three, then Roberts called together those remaining. After a considerable struggle, Holy Spirit descended and he got home around 7.00am. He was awakened at around 11.00am with his mother screaming out that she was dying. She had felt so bad about leaving the chapel before the end of the meeting that Evan helped her in prayer until she found peace. On the Wednesday he was invited to hold the service at Brynteg Congregational Chapel, Gorseinon, and Holy Spirit broke out there as well. He was in the same place on Thursday night and it was a very powerful meeting with people coming from further afield. For the first time a reporter from the Western Mail was at a meeting. The newspaper reported that shops were closing early to ensure that the owners got a seat and the tin and steel workers were arriving in their work clothes.

Some students from Ammanford came to one of the meetings, caught the fire and started meetings at Bethany Chapel, but the fire was not of the same intensity, so they invited Roberts to come.

On the Friday the meeting was held at Moriah chapel, Loughor again and over 650 attended, including several ministers from surrounding districts. On Saturday a long article was published in the Western Mail that was very sympathetic to what was happening in the meetings. This article brought about an invitation from a chapel in Aberdare for Roberts to preach on the Sunday; an invitation he accepted. By now prayer meetings were being held in some houses in Loughor all day long. Two girls went to hold open air meetings near some public houses in Gorseinon and some young people went to evangelise some gypsies who had encamped near Loughor. In both places there were salvations.

That night the new chapel was filled long before the time to begin the service, so Roberts asked his friend Sydney Evans, who had just returned from Newcastle Emlyn, to take the overflow into the old chapel. However, in minutes that was full as well. Several of the people there that night had come to scoff, but ended up giving their lives to Christ. It was past 5.00am when the people went home.

During these two weeks the fire was burning in other parts of Wales. Joseph Jenkins had a good deal of success with his meetings and he arrived at Ammanford to find the fire that had started beginning to wane. After a series of meetings the fire rekindled and when Seth Joshua arrived on November 19th the fire burst into flame. Another flame of the Revival was in Tonypandy in the Rhondda. Holy Spirit had been stirring since the beginning of 1904 at Trinity, an English speaking (the other chapels so far mentioned were Welsh speaking) Calvinistic Methodist chapel. By October 600 had given their lives to Christ.

It is difficult to work out the importance of Evan Roberts to the Revival. I know that when I first started reading about the 1904 Revival I thought that Evan Roberts was the Revival, but this is clearly not the case. Most people believe that New Quay was the start in February 1904, a full seven months before he was baptised by the Spirit. Having said that there are reports of loacalised revivals even before February, but they do not seem to have spread out from their base. If you have read a selection of the Welsh biographies on this website you will know that Wales probably had a revival going on somewhere, every year from 1735 all the way through to 1904.

Even though localised revivals can be traced to other parts of Wales before February 1904, I do not believe that they were part of the move of God that is known as the Welsh Revival. I believe that New Quay was the start, with Jenkins and the young women of New Quay going out from their base to spread the fire to other parts. When God decides to move in this way it appears that the revival atmosphere is over a large area, but only a few people are able to ignite the flame. The way I see it is that Joseph Jenkins was used to ignite the original flame, but it was left to Evan Roberts to stoke the fire so that it spread powerfully over the nation. In some places Roberts brought the flame with him, in others it had travelled before him, either because someone had visited a place where the fire was burning and taken it back, or because someone had realised that revival was in the atmosphere and pulled it down to earth. Seth Joshua and Sidney Evans also stoked the fire and took it around the nation, but probably not to the level of Roberts. There were also other men who carried the fire from place to place in a lesser way. It is my view that the key to revival is to recognise that it is in the atmosphere, that it is in God’s plan, and then to have such a relationship with the Lord that you can pull heaven down to the earth.

The question is; can a local revival be stoked into a national one? If a local pastor discerns that revival is in the atmosphere and he pulls it down through prayer into his church revival is unlikely to go out from there unless he decides to leave his church, to carry that revival around the country. Another way it can spread is for some gifted person, who has experienced the revival, to take it beyond the walls of the church or the local area. It takes quite a special person to do this. In either case whoever carries the revival must have a close relationship with the Lord, be sensitive and discerning of the Spirit, have leadership gifts, be completely focused and dedicated to the task, have great energy and passion and be able to capture the attention of a large number of people through teaching and prayer. Basically, it must be someone whom Holy Spirit can direct, so that the meetings conform precisely to His purposes. I think that the Lord sometimes pours out His blessings purely for a local church, but I also believe that many times the revival could be spread abroad. Compared with the times of revival that Wales has experienced so often in the past, today, with communication and travel being so instant, what would have been only a local revival can now become a national or international one.

I am not going to describe, in any detail, where the revival spread. You can read this in two of the books mentioned below. Suffice it to say the rest of Britain only received a scattering of blessing. The Revival was felt all around the world to some extent, especially in India. The most significant connection to the Welsh Revival was the Azusa Street Revival of 1906 in California. There does not seem to be a recordable direct connection, but the writings of Frank Bartleman leaves no doubt that he and others were inspired by what happened in Wales. The Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles began the Pentecostal movement which now numbers in the hundreds of millions worldwide.

We return to the story of Evan Roberts. It seems that the high profile of Roberts during the revival was partly due to the press. This was the first revival where the press took such a role. There were many articles written in the newspapers during the 1859 revival, but in 1904 the newspapers followed Roberts around and wrote about him consistently. He was a charismatic, good-looking young man, so small wonder the press followed him more than anyone else.

Roberts’ first tour started at Trecynon on November 13th and by November 26th the whole of Wales knew about the Revival. At Cilfynydd all the chapels in the town were full and work in the collieries was suspended for the sake of the meetings. The following day was Sunday, and news came from various directions of many conversions, and open air meetings were held in scores of places. Within four weeks the revival had started in many parts without the help of Roberts or anyone else. Young people would go onto railway platforms to sing and pray; prayer meetings were held on trains and many were converted. Public houses and beer clubs were empty; old debts were repaid, family feuds were healed; drunks and gamblers were praying in the services and the chapels throughout Glamorganshire were full every night. Drunkenness declined substantially with convictions falling in Glamorganshire by almost half. It is said that the pit ponies could no longer understand the miner’s instructions because of the absence of oaths and curses.

I have calculated that Roberts held close to fifty services in the first month of the revival. During the first week he held only one meeting a day, but after that it was often three services a day and during that month he only had one day off. This is a gruelling programme, especially as some of the meetings went on for four or five hours, and he also had to travel from town to town. The emotion that Roberts expended at each service was enormous, so he must have been exhausted even this early in the revival, despite the refreshing touch of Holy Spirit. These meetings were all very powerful and the number of people attending was great. Often when the main chapel was full, the chapel of another denomination would open and when that was full another would open. Sometimes there were services going on at three chapels at the same time. Roberts might speak at all three or leave the other two to other leaders. Often he would split the services of the day between the different chapels in the town.

Roberts did meetings every day except one between October 30th and Dec 23rd. By the end of the year South Wales was ablaze with, according to the Western Mail, at least thirty four thousand converts, although many towns had not sent in their returns. In North Wales there were a few fires, but it was not ablaze. Roberts had a few days at home for Christmas, although they were not restful as many came to see him. After that he travelled again for a little over two months, returning home early in March. On returning home he gave all the money he had accumulated away so that he had no money in his pocket when he went to Liverpool on March 29th. He visited the Welsh community there for almost three weeks and around 750 converts came to the Lord during his stay there.

Roberts was in Anglesey for most of June, but the meetings were not as successful as those down South, mainly because the fire had already been burning there for some time. By the autumn of 1905 Roberts’ influence had waned; he was not really needed anymore as he had done his job. People had heard of the revival all over Wales, and groups of mainly young people started prayer meetings elsewhere to pray in what was happening. The fire fell in many areas. The 100,000 souls that Roberts had prayed for came in, with all denominations benefiting.

By January 1906 he was run down and went to stay with Mr and Mrs Penn-Lewis in Leicester. He had a breakdown for a time, only appearing in public occasionally. In 1907 he devoted himself to prayer. From 1930 until his death in 1951, he lived in Cardiff. He was buried in Moriah Chapel cemetery, Loughor.

This is a very short account of the 1904 Revival and the life of Evan Roberts. There are several questions that do not seem to have satisfactory answers. Why did Roberts go and stay in Leicester? Why did he stay so long in the house of the Penn-Lewis’? Why did he not spread the fire to England? Perhaps God’s timing was that the general revival was to stop in the autumn of 1905 (some fires were still burning in 1906). The long-term benefits of the 1904 Revival were sadly cut short by the 1914-18 War, where many of the young converts were killed.

There is a lot written about the 1904 Revival. If you want to read a detailed account of Roberts early life and his part in the revival, get from your library ‘Evan Roberts, The Great Welsh Revivalist and His Work’ By D M Phillips. Phillips accompanied him to many of his meetings and he includes many letters and detailed accounts of where and when he spoke. He describes Roberts in a lot of detail. The book was published in 1906. A more concise version is ‘The Welsh Revival of 1904’ by Eifion Evans, published in 1969 by Bryntirion Press. A wider account of the revival is ‘Fire on the Altar’ by Noel Gibbard, published in 2005 by Bryntirion Press.